Beneath the ocean’s surface, a quiet revolution is taking place. Artificial reefs are reshaping marine ecosystems, creating underwater sanctuaries where fish populations flourish and biodiversity thrives in once-barren areas.

The ocean’s health has been declining for decades due to overfishing, climate change, and habitat destruction. Marine scientists and conservationists have discovered that strategic placement of artificial structures underwater can reverse some of this damage. These engineered habitats are becoming beacons of hope for ocean recovery, demonstrating that human intervention, when thoughtfully executed, can heal rather than harm our marine environments.

🌊 Understanding the Science Behind Artificial Reefs

Artificial reefs function as three-dimensional structures that mimic natural reef systems. When placed strategically on the ocean floor, these installations provide essential services that fish and marine organisms desperately need. The surfaces offer attachment points for algae, coral larvae, and invertebrates, which form the foundation of complex food webs.

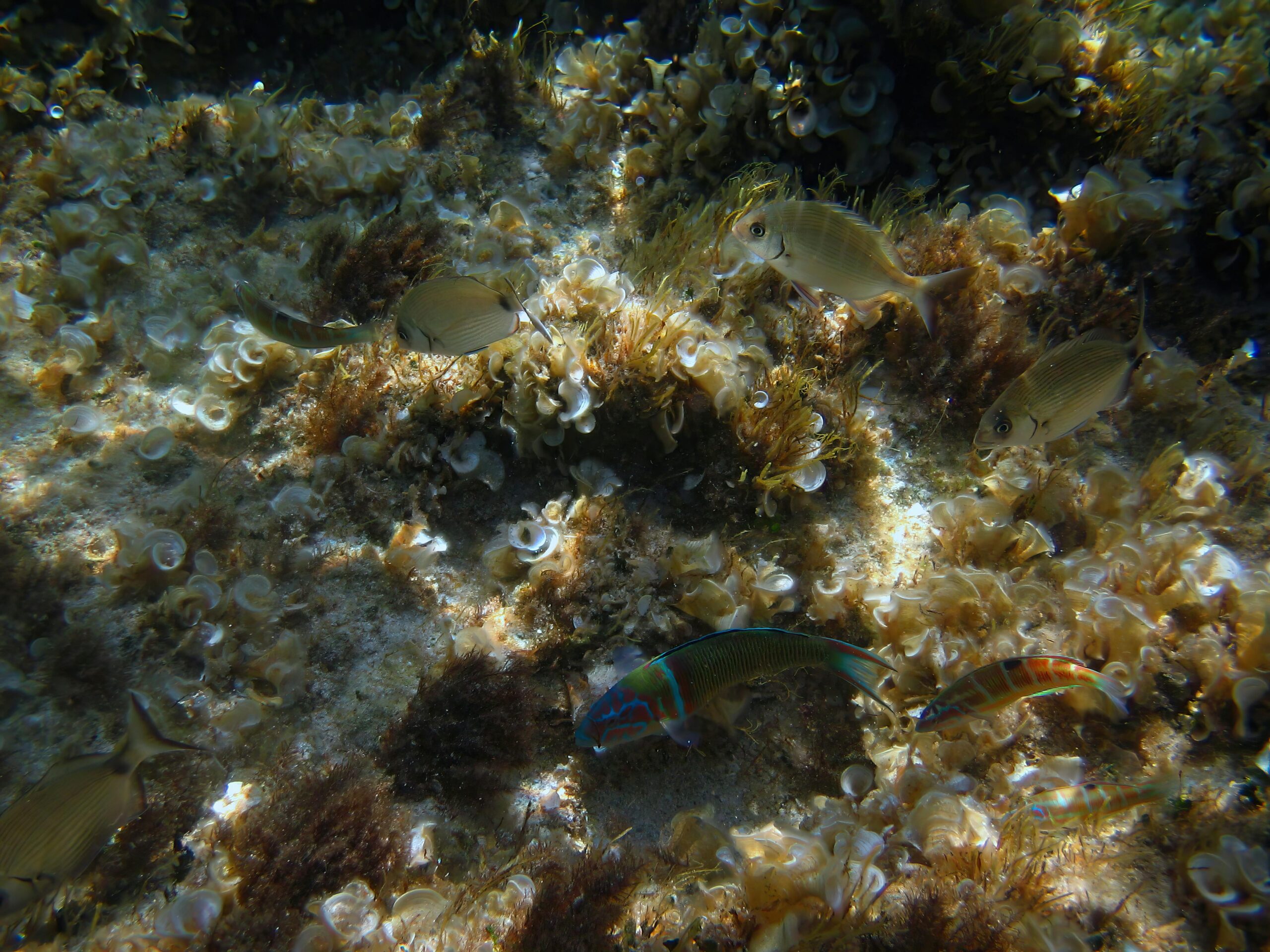

The transformation begins almost immediately after deployment. Within weeks, microorganisms colonize the surfaces, followed by algae and small invertebrates. These pioneer species attract herbivorous fish, which in turn draw predators. Within months, a barren artificial structure can support hundreds of species, creating a vibrant ecosystem where none existed before.

Water flow patterns around artificial reefs create upwelling zones that concentrate nutrients and plankton. These productive areas become feeding stations for filter feeders and planktivorous fish. The structural complexity provides crucial hiding spots for juvenile fish, dramatically increasing their survival rates during vulnerable life stages.

The Materials That Make a Difference

Not all materials are suitable for artificial reef construction. Marine engineers carefully select substances that are environmentally safe, durable, and conducive to marine life colonization. Concrete remains one of the most popular choices due to its pH-neutral composition after curing and its ability to support coral settlement.

Decommissioned vessels, carefully cleaned of pollutants, have become popular reef materials. These ships provide massive surface areas and complex internal spaces that different species can occupy. The USS Oriskany in the Gulf of Mexico and the HMCS Yukon off British Columbia are prime examples of successful ship reefs attracting both marine life and dive tourism.

Specialized reef balls—dome-shaped concrete structures with strategically placed holes—optimize water flow and provide diverse microhabitats. Their design considers the needs of various species, from lobsters seeking dark crevices to fish requiring open swimming spaces nearby.

🐠 The Biodiversity Explosion: From Desert to Oasis

The biological transformation of artificial reefs is nothing short of remarkable. Studies from artificial reefs worldwide document exponential increases in fish abundance and species diversity within the first year of deployment. What was once a sandy or muddy bottom becomes a bustling metropolis of marine life.

Fish populations increase through two mechanisms: attraction and production. The attraction effect draws existing fish from surrounding areas to the new structure, while the production effect refers to actual population growth through improved survival and reproduction rates. Research indicates that well-designed artificial reefs contribute significantly to both processes.

Different reef structures attract different community assemblages. Vertical relief structures attract pelagic species like jacks and barracuda, while low-profile reefs become nurseries for bottom-dwelling species. This diversity allows managers to design reefs targeting specific conservation or fisheries goals.

Key Species That Benefit Most

Certain fish families show particularly strong affinities for artificial structures. Groupers, snappers, and sea bass quickly adopt artificial reefs as home territories. These economically important species benefit from the increased hunting opportunities and shelter that reefs provide.

Schooling species like sardines, herrings, and anchovies form massive aggregations around artificial reefs. These baitfish concentrations create spectacular feeding opportunities for larger predators, establishing dynamic food chains that ripple through the entire ecosystem.

Reef-associated invertebrates experience population booms on artificial structures. Lobsters, crabs, octopuses, and countless mollusk species find ideal conditions for growth and reproduction. These invertebrate communities support commercial fisheries while providing essential ecosystem services like water filtration.

🔧 Engineering Oceans: Design Principles and Deployment Strategies

Creating successful artificial reefs requires sophisticated planning that considers oceanographic conditions, ecological objectives, and long-term sustainability. Marine engineers work alongside biologists to design structures that maximize ecological benefits while minimizing environmental risks.

Site selection is critical. Ideal locations feature appropriate depth ranges, suitable substrate for anchoring, favorable current patterns, and proximity to natural reefs or fish populations. Environmental impact assessments ensure deployments won’t harm existing ecosystems or interfere with navigation, fishing grounds, or underwater infrastructure.

Structural design incorporates principles of biomimicry, replicating features of natural reefs that fish find attractive. Complexity is key—multiple levels, varied hole sizes, overhangs, and internal chambers accommodate diverse species with different behavioral needs.

The Deployment Process

Deploying artificial reefs involves precise coordination between marine construction teams, environmental monitors, and regulatory agencies. Large structures like ships require tugboats, specialized positioning equipment, and controlled sinking procedures to ensure they settle correctly on the seafloor.

Smaller modular reefs can be deployed from barges or boats using cranes or cables. GPS technology ensures accurate placement according to reef plans. Some projects deploy reefs in clusters or lines to create reef complexes that enhance connectivity between marine populations.

Post-deployment monitoring tracks colonization rates, species composition, and structural integrity. Underwater cameras, dive surveys, and acoustic monitoring provide data that inform future reef designs and help managers assess whether projects meet their intended goals.

🌍 Global Success Stories: Artificial Reefs Around the World

Japan leads the world in artificial reef deployment, with over 120 million cubic meters of structures placed since the 1950s. Their extensive reef systems support commercial fisheries and have become cultural landmarks. The Japanese approach emphasizes long-term commitment and adaptive management based on decades of monitoring data.

The Persian Gulf nations have invested heavily in artificial reefs as part of marine conservation strategies. The UAE’s reef programs combine conservation with tourism development, creating dive destinations that generate revenue while rebuilding depleted fish stocks.

Florida’s artificial reef program ranks among the most extensive in North America. With thousands of permitted reef sites, Florida uses everything from concrete modules to decommissioned military vessels. These reefs support recreational fishing worth hundreds of millions of dollars annually while providing critical habitat for threatened species like goliath grouper.

Europe’s Innovative Approaches

European countries are pioneering artificial reefs designed for multiple purposes. The Netherlands deploys reefs that simultaneously provide fish habitat, protect offshore infrastructure, and generate substrate for sustainable aquaculture. This integrated approach maximizes return on investment while addressing multiple marine management challenges.

Mediterranean artificial reefs focus on rebuilding populations of overfished species. Italy, Spain, and France have established reef networks in areas where bottom trawling has devastated natural habitats. Early results show promising recovery of commercial fish stocks and benthic communities.

The United Kingdom is experimenting with artificial reefs designed specifically for native oyster restoration. These reefs provide settlement surfaces for oyster larvae while creating habitat complexity that benefits dozens of associated species. The oysters themselves contribute water filtration services, improving overall ecosystem health.

⚖️ Addressing Controversies and Ecological Concerns

Despite their benefits, artificial reefs remain controversial in some circles. Critics argue that reefs may simply concentrate existing fish rather than increasing overall populations, making concentrated schools vulnerable to overfishing. This concern has merit in areas lacking adequate fisheries management, highlighting the need for reef deployment and fishing regulations to work together.

The attraction versus production debate continues among marine scientists. While some studies show artificial reefs primarily attract mobile fish from surrounding areas, others document genuine population increases through enhanced recruitment and survival. The truth likely varies by location, species, and reef design, emphasizing the importance of site-specific research.

Potential negative impacts include altered sediment transport patterns, introduction of invasive species, and accumulation of fishing gear. Responsible reef programs address these concerns through careful site selection, monitoring protocols, and adaptive management that adjusts practices based on observed outcomes.

Environmental Safeguards and Best Practices

Modern artificial reef programs follow strict environmental guidelines. Materials undergo toxicity testing to ensure they won’t leach harmful substances. Vessels are meticulously cleaned, removing oils, PCBs, and other contaminants before deployment.

Reef locations are selected to complement rather than replace natural habitats. Programs avoid placing artificial structures where they might damage existing reefs or seagrass beds. Buffer zones around sensitive areas ensure reefs enhance rather than compromise regional biodiversity.

Transparent monitoring and public reporting build trust and allow continuous improvement. Successful programs publish data showing ecological outcomes, acknowledge shortcomings, and adjust strategies accordingly. This scientific rigor separates legitimate conservation efforts from well-intentioned but poorly executed projects.

🎣 Balancing Conservation with Recreational and Commercial Fishing

Artificial reefs serve multiple stakeholders, creating both opportunities and management challenges. Recreational anglers value reefs as fishing hotspots, while commercial fishers see them as productive fishing grounds. Conservationists view them as habitat restoration tools. Balancing these interests requires thoughtful regulation and stakeholder engagement.

Many jurisdictions establish fishing restrictions on artificial reefs during critical periods. Seasonal closures during spawning seasons allow fish populations to reproduce before harvest. Size and bag limits prevent overfishing of concentrated populations. Some reefs become marine protected areas where fishing is permanently prohibited, serving as source populations that replenish surrounding waters.

The economic value of artificial reefs extends beyond direct fishing benefits. Dive tourism generates substantial revenue in regions with accessible reef sites. These economic incentives create constituencies that support marine conservation, demonstrating how properly managed reefs can align economic and environmental interests.

Community Involvement and Local Stewardship

Successful artificial reef programs engage local communities from planning through maintenance. Fishers provide valuable knowledge about local oceanography and fish behavior. Dive operators contribute monitoring data and report structural problems. Community ownership increases compliance with regulations and creates long-term stewards for reef sites.

Educational programs connect schools and youth groups with artificial reefs. Students participate in reef design competitions, deployment events, and monitoring activities. These experiences build ocean literacy and create future generations committed to marine conservation.

Volunteer reef monitoring programs leverage citizen science to expand data collection beyond what professional researchers can accomplish alone. Trained volunteers conduct fish counts, photograph species, and document reef conditions. This distributed monitoring network provides valuable longitudinal data while deepening public connection to marine ecosystems.

🔮 Future Horizons: Innovation and Climate Adaptation

Climate change adds urgency to artificial reef development while presenting new challenges. Rising ocean temperatures stress natural coral reefs, making artificial structures increasingly important as refugia and alternative habitats. Future reef designs must consider climate projections to ensure long-term viability.

Researchers are developing thermally resilient artificial reefs using materials that moderate temperature fluctuations. Some designs incorporate shading elements or promote upwelling of cooler deep water. These climate-smart reefs may provide critical habitat as ocean warming intensifies.

Three-dimensional printing technology is revolutionizing reef construction. Custom-designed structures can be printed from materials mimicking the chemical composition and texture of natural limestone. This precision allows optimization for specific species or environmental conditions, potentially improving colonization success rates.

Integration with Renewable Energy Infrastructure

Offshore wind farms present opportunities for dual-purpose infrastructure that generates clean energy while creating marine habitat. Turbine foundations essentially function as artificial reefs, and intentional enhancement through additional structures could maximize biodiversity benefits. This integration represents efficient use of ocean space and investment.

Wave and tidal energy installations similarly offer reef-building potential. Anchoring systems and structural components provide hard substrate in locations that might otherwise lack it. As renewable ocean energy expands, thoughtful design can multiply ecological benefits alongside carbon-free electricity generation.

Aquaculture facilities are incorporating artificial reef designs that support wild fish populations while producing farmed seafood. These hybrid systems create habitat complexity around fish pens, attracting wild species that benefit from food spillage and structural protection. Properly managed, this integration could make aquaculture more ecologically beneficial.

💡 Measuring Success: Metrics That Matter

Defining and measuring artificial reef success requires clear objectives and appropriate metrics. Biomass increases, species diversity indices, and recruitment rates provide quantitative data on ecological performance. Economic metrics include fishing yields, tourism revenue, and employment generation.

Long-term monitoring is essential because reef communities continue evolving for years after deployment. Initial colonization patterns may differ dramatically from mature community structures. Sustained funding for monitoring programs ensures managers understand whether reefs meet long-term objectives.

Comparative studies between artificial and natural reefs help calibrate expectations and improve designs. While artificial structures may never perfectly replicate natural reef complexity, understanding what they do well and where they fall short guides future improvements.

Technology Enhancing Monitoring Capabilities

Underwater drones equipped with high-definition cameras allow comprehensive documentation of reef conditions without disturbing marine life. These remotely operated vehicles can survey deeper reefs beyond recreational diving limits, expanding our understanding of artificial reef ecology across depth gradients.

Acoustic telemetry tracks individual fish movements around artificial reefs. Tagged fish reveal how they use reef structures, how far they range, and whether they remain resident or move between sites. This behavioral data informs spacing decisions for reef networks and helps assess whether reefs function as isolated habitat patches or connected nodes in larger seascapes.

Environmental DNA sampling detects species presence through genetic material shed into seawater. This technique identifies rare or cryptic species that visual surveys might miss, providing comprehensive biodiversity assessments with less effort than traditional methods. As eDNA technology improves, it will become increasingly valuable for reef monitoring programs.

🌟 The Path Forward: Scaling Success Responsibly

Artificial reefs represent powerful tools for marine restoration, but they’re not panaceas. Success requires integration with broader ocean management strategies addressing pollution, overfishing, and climate change. Reefs work best as components of comprehensive conservation programs rather than standalone solutions.

Scaling artificial reef deployment to meet global needs demands increased investment in research, monitoring, and adaptive management. Funding mechanisms that capture economic benefits—through fishing license fees, tourism taxes, or carbon offset programs—can sustain programs long-term.

International cooperation and knowledge sharing accelerate progress. Countries with extensive reef experience can mentor emerging programs, preventing others from repeating mistakes while spreading proven techniques. Global databases documenting reef locations, designs, and outcomes would advance the entire field.

Artificial reefs demonstrate humanity’s capacity to reverse environmental damage when we combine scientific knowledge, engineering innovation, and sustained commitment. As ocean challenges intensify, these underwater havens offer tangible hope that we can rebuild what we’ve depleted and create resilient marine ecosystems for future generations. The transformation of barren seafloors into thriving fish habitats proves that with thoughtful intervention, we can become architects of ocean recovery rather than agents of decline.