The ocean is a vast, interconnected world where countless marine species embark on extraordinary journeys spanning thousands of miles. These migrations represent some of nature’s most remarkable phenomena, driven by survival instincts and environmental cues.

From the smallest plankton to the largest whales, marine creatures traverse invisible pathways across our planet’s waters, following routes perfected over millions of years of evolution. Understanding these migration patterns reveals not only the incredible adaptability of ocean life but also the delicate balance of our marine ecosystems and the urgent need for their protection in an era of climate change.

🌊 The Science Behind Marine Migration

Marine migration is a complex biological phenomenon influenced by multiple environmental factors. Ocean temperatures, salinity levels, food availability, and reproductive needs all play crucial roles in determining when and where marine species travel. Scientists have discovered that many species possess remarkable navigational abilities, using the Earth’s magnetic field, ocean currents, celestial cues, and even chemical signals to find their way across vast distances.

The study of marine migration has been revolutionized by modern technology. Satellite tracking devices, acoustic tags, and genetic analysis have provided unprecedented insights into the movements of ocean creatures. These technological advances have revealed migration routes that were previously unknown and have challenged long-held assumptions about marine life behavior.

Oceanographic conditions create natural highways in the sea. Major current systems like the Gulf Stream, the Kuroshio Current, and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current serve as conveyor belts for migrating species. These currents not only provide energy-efficient travel routes but also concentrate nutrients and prey, making them essential corridors for marine life.

The Epic Journeys of Marine Mammals 🐋

Marine mammals undertake some of the longest migrations in the animal kingdom. Gray whales hold the record for the longest mammalian migration, traveling approximately 12,000 miles round trip between their feeding grounds in the Arctic waters and breeding lagoons in Baja California, Mexico. This incredible journey takes place twice annually, with mothers teaching their calves the route through generational knowledge passed down over millennia.

Humpback whales perform similarly impressive migrations across all major oceans. These gentle giants spend summers feeding in polar waters where krill and small fish are abundant, then travel to tropical or subtropical waters to breed and give birth. During these journeys, humpbacks can travel up to 5,000 miles, often fasting for months while relying on stored energy reserves.

Elephant seals demonstrate extraordinary diving capabilities during their migrations. Northern elephant seals travel from California’s coast to feeding grounds in the North Pacific, spending eight to ten months at sea. During this time, they dive continuously to depths exceeding 5,000 feet, coming to the surface only briefly to breathe before plunging back into the darkness.

Navigation Mysteries of the Deep

How marine mammals navigate across featureless ocean expanses remains partially mysterious. Research suggests they use a combination of methods including echolocation, memory of seafloor topography, detection of water temperature gradients, and possibly sensing the Earth’s magnetic field. Some species may also use the positions of stars and the sun for orientation, much like ancient human mariners.

Fish Migrations: Synchronized Movements Across Oceans 🐟

Fish species display diverse migration patterns ranging from short coastal movements to transoceanic odysseys. Atlantic bluefin tuna are among the most impressive fish migrants, crossing the entire Atlantic Ocean multiple times during their lifetimes. These powerful swimmers can maintain speeds of 40 miles per hour and travel thousands of miles between spawning grounds in the Mediterranean Sea or Gulf of Mexico and feeding areas in the North Atlantic.

Salmon migrations represent one of nature’s most iconic journeys. These anadromous fish are born in freshwater streams, migrate to the ocean to mature, then return to their exact birthplace to spawn. Pacific salmon navigate using olfactory memory, literally smelling their way back to their natal streams after years at sea. This remarkable homing ability demonstrates the sophistication of fish sensory systems.

Eels present an opposite migration pattern called catadromy. European and American eels spend most of their adult lives in freshwater rivers and lakes but travel thousands of miles to the Sargasso Sea in the Atlantic Ocean to spawn. After breeding, adult eels die, while their larvae drift on ocean currents back toward coastal areas, taking up to three years to reach freshwater habitats.

Schooling Behavior and Mass Movements

Many fish species migrate in massive schools, creating some of the ocean’s most spectacular sights. The sardine run along South Africa’s coast involves billions of fish moving northward along the eastern coastline, creating a feeding frenzy that attracts dolphins, sharks, whales, and seabirds. These aggregations serve protective functions, reducing individual predation risk while maximizing reproductive success.

Sea Turtles: Ancient Navigators of the Ocean 🐢

Sea turtles are among the ocean’s most accomplished navigators, with migration patterns that span entire ocean basins. Loggerhead turtles hatched on beaches in Japan have been tracked swimming across the entire Pacific Ocean to feeding grounds off Baja California, Mexico—a journey of over 7,500 miles. They later return across the Pacific to their natal beaches to nest, demonstrating remarkable site fidelity.

Leatherback sea turtles undertake the longest migrations of any reptile, traveling up to 10,000 miles annually. These massive creatures, which can weigh up to 2,000 pounds, follow jellyfish blooms across oceans, diving to depths of 4,000 feet in search of prey. Their migrations connect tropical nesting beaches with temperate and even sub-Arctic feeding areas.

The navigational abilities of sea turtles are extraordinary. Hatchlings emerging from nests possess an innate ability to orient themselves using the Earth’s magnetic field, essentially having a built-in GPS system. This magnetic map allows them to navigate ocean currents and eventually return to nesting sites after decades at sea—a journey most complete in total darkness after emerging from eggs buried in sand.

Sharks: Silent Travelers of the Deep 🦈

Sharks are highly mobile predators with migration patterns that reflect their role as apex predators in marine ecosystems. Great white sharks undertake extensive migrations between coastal areas and open ocean. Sharks tagged off California have been tracked traveling to an area dubbed the “White Shark Café” halfway between Baja California and Hawaii, where they spend months in deep water before returning to coastal hunting grounds.

Whale sharks, the world’s largest fish, migrate across tropical oceans following plankton blooms and seasonal aggregations of spawning fish. Despite their massive size—up to 40 feet long—these gentle filter feeders can travel thousands of miles annually. Satellite tracking has revealed that whale sharks dive to depths exceeding 6,000 feet, possibly to access deep-water prey or navigate using temperature gradients.

Basking sharks, another filter-feeding species, perform seasonal migrations in the North Atlantic, appearing near coasts during summer months to feed on plankton blooms, then disappearing to offshore areas during winter. Recent tracking studies have revealed that these sharks dive to considerable depths during winter months, challenging earlier assumptions that they hibernated on the seafloor.

The Invisible Migrations: Plankton and Small Creatures 🦐

Not all migrations involve large, charismatic species. The largest migration on Earth occurs daily as countless zooplankton, small fish, and invertebrates participate in vertical migration. Every night, trillions of creatures rise from deep waters toward the surface to feed, then descend before dawn to avoid predators. This daily movement transfers massive amounts of carbon and nutrients through ocean layers, playing a crucial role in global nutrient cycling and climate regulation.

Krill, small shrimp-like crustaceans, perform both vertical daily migrations and horizontal seasonal migrations. Antarctic krill populations migrate hundreds of miles following the seasonal advance and retreat of sea ice. These movements are critical because krill form the foundation of Antarctic food webs, supporting whales, seals, penguins, and countless fish species.

Squid species exhibit fascinating migration patterns, with some species traveling between deep ocean habitats and coastal waters for breeding. The Humboldt squid of the Eastern Pacific undergoes nightly vertical migrations of up to 2,000 feet, rising to feed on fish and crustaceans before returning to deep, oxygen-poor waters during daylight hours.

Climate Change: Disrupting Ancient Pathways 🌡️

Rising ocean temperatures are fundamentally altering marine migration patterns that have existed for millennia. Many species are shifting their ranges poleward in search of cooler waters, disrupting established ecosystems and creating novel species interactions. Fish stocks that traditionally supported coastal communities are moving beyond traditional fishing grounds, creating economic and food security challenges.

Changes in ocean chemistry, particularly acidification and deoxygenation, are affecting the sensory abilities of migrating species. Studies have shown that elevated carbon dioxide levels can impair the olfactory systems of salmon and other fish, potentially disrupting their ability to navigate to spawning grounds. This represents an insidious threat to migration success that may not be immediately visible but could have devastating long-term consequences.

Sea ice loss in polar regions is particularly impactful for species that depend on ice-edge ecosystems. Polar bears, though not purely marine animals, rely on sea ice to hunt seals. Similarly, many Arctic fish species time their migrations to coincide with ice breakup patterns that are becoming increasingly unpredictable. The loss of sea ice habitat also affects the entire Arctic food web, from ice algae to whales.

Human Impacts on Migration Routes ⚓

Beyond climate change, human activities create numerous obstacles for migrating marine species. Commercial fishing operations, both legal and illegal, remove massive numbers of fish and bycatch species from migration routes. Longlines, drift nets, and trawls kill millions of non-target animals annually, including sea turtles, dolphins, sharks, and seabirds that follow migration pathways.

Ship strikes represent a significant mortality factor for large marine mammals. Major shipping lanes often intersect with whale migration routes, resulting in collisions that injure or kill whales. Efforts to reduce strikes include vessel speed restrictions in critical areas, although enforcement remains challenging.

Noise pollution from shipping, sonar, and offshore development interferes with the communication and navigation abilities of marine species. Many whales and dolphins rely on sound for communication across vast distances, and anthropogenic noise can mask these signals. There is also evidence that intense underwater noise may disorient migrating species, potentially causing strandings or diverting animals from optimal routes.

Plastic pollution poses both immediate and long-term threats. Sea turtles mistake plastic bags for jellyfish, their natural prey, leading to ingestion that can be fatal. Microplastics are now found throughout the ocean, being consumed by species at all trophic levels. The long-term effects of microplastic ingestion on migration success and overall health remain areas of active research.

Conservation Efforts: Protecting Ocean Highways 🛡️

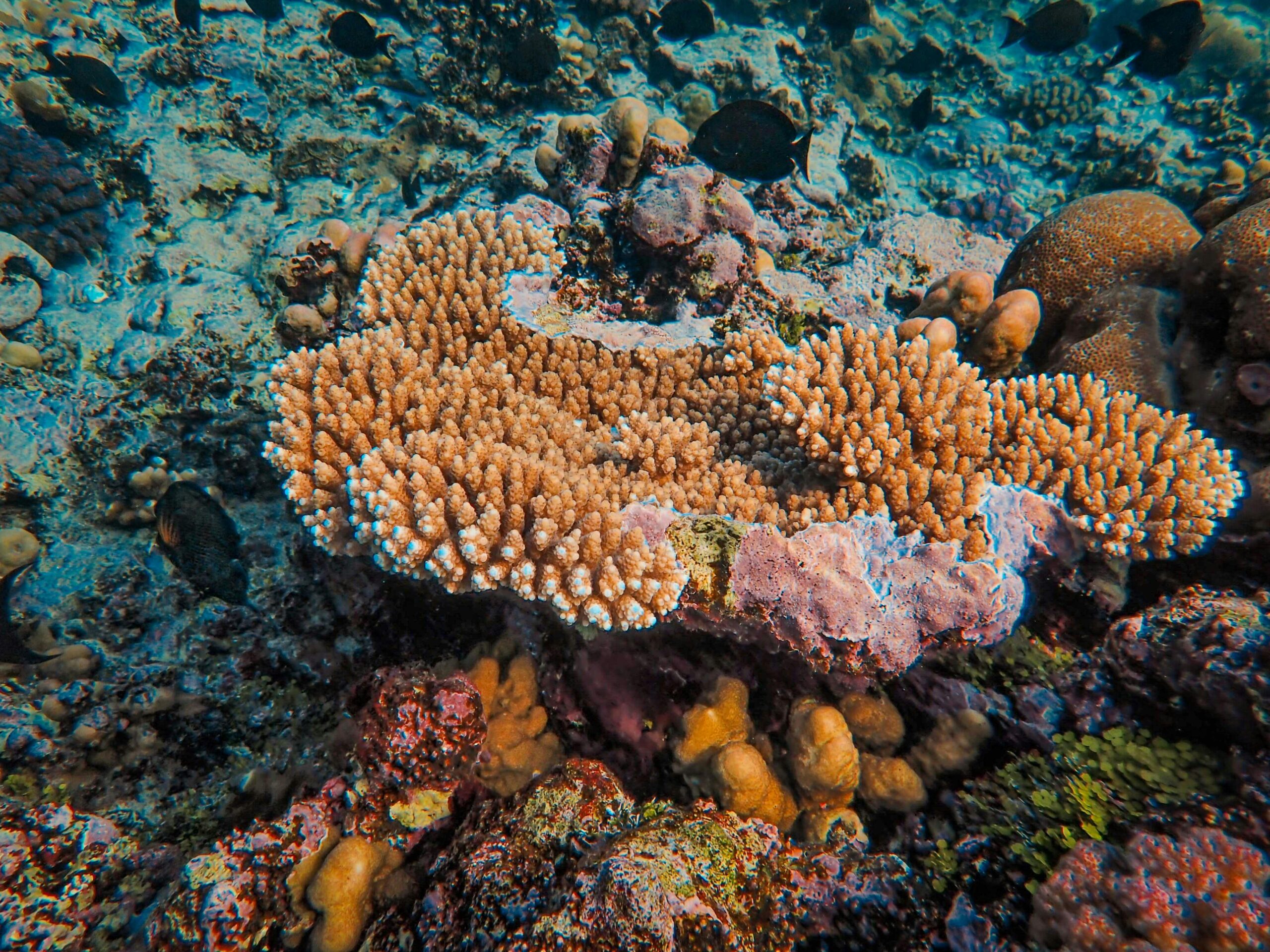

Protecting marine migration routes requires international cooperation because these pathways cross political boundaries. Marine protected areas (MPAs) are being established to safeguard critical habitats along migration routes. The Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in Hawaii protects important feeding and breeding grounds for numerous species, including Hawaiian monk seals, green sea turtles, and multiple whale species.

Dynamic ocean management represents an innovative approach to conservation. Rather than static protected areas, this strategy uses real-time data on species locations to implement temporary protections where and when they’re most needed. Fishing closures can be activated when satellite tracking reveals whale aggregations, or shipping lanes can be temporarily adjusted to avoid turtle nesting seasons.

International agreements like the Convention on Migratory Species provide frameworks for cooperative conservation. These treaties recognize that protecting migrating species requires coordinated action across their entire range. Success stories include the recovery of humpback whale populations following the end of commercial whaling, demonstrating that international cooperation can achieve remarkable conservation outcomes.

Community-based conservation programs engage coastal populations in protecting critical migration stages. In Costa Rica, former egg poachers have become sea turtle conservation leaders, protecting nesting beaches and educating tourists. Such programs recognize that local communities must benefit from conservation efforts for them to be sustainable long-term.

Technology Illuminating Hidden Journeys 📡

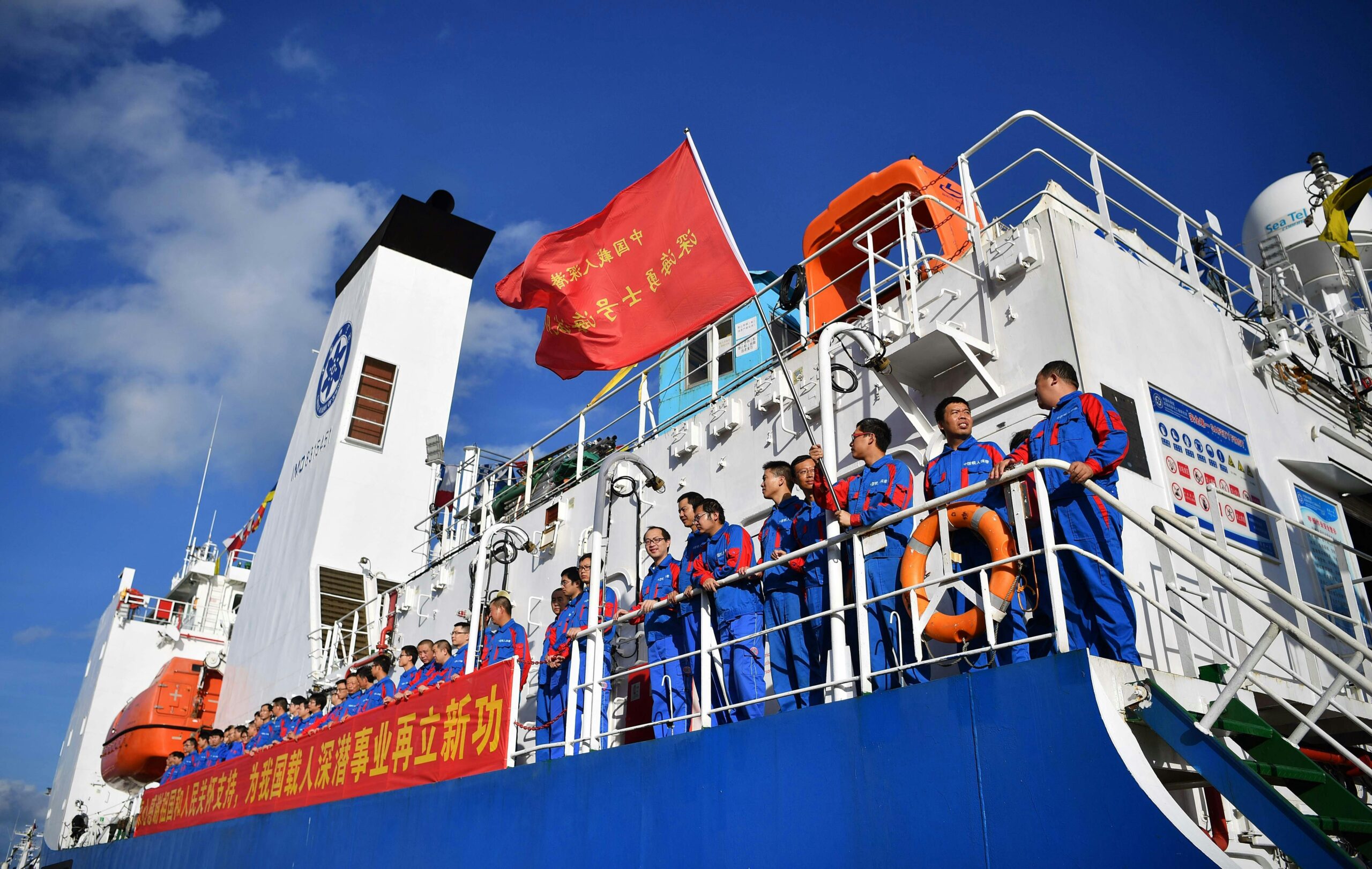

Satellite telemetry has revolutionized our understanding of marine migrations. Tags that transmit data when animals surface provide detailed information on movement patterns, dive behavior, and habitat use. These devices have revealed surprising behaviors, such as deep-diving by species not previously known to reach extreme depths, and migration routes that cross entire ocean basins.

Genetic analysis provides insights into population structure and migration connectivity. By analyzing DNA from tissue samples, researchers can determine whether different populations mix during migrations or remain genetically distinct. This information is crucial for management decisions, helping identify discrete populations that require separate conservation strategies.

Acoustic monitoring networks consist of underwater receivers that detect tagged animals as they pass by. These networks are particularly useful for tracking species that don’t surface regularly, including many shark and fish species. Global arrays of acoustic receivers create a worldwide tracking system that has revealed previously unknown migration pathways.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis is an emerging tool that detects species presence by analyzing water samples for genetic material shed by organisms. This non-invasive technique can identify which species use particular areas and when, providing migration timing information without requiring direct animal capture or observation.

The Future of Marine Migrations 🔮

The coming decades will be critical for marine migrations. Climate models predict continued warming and ocean changes that will further alter species distributions and migration timing. Some species will adapt by shifting ranges or adjusting migration schedules, while others may face population declines or local extinctions if they cannot adapt quickly enough.

Emerging technologies promise new insights into migration ecology. Miniaturization of tracking devices means even small species can now be monitored. Autonomous underwater vehicles and drones provide new platforms for observing marine life without human presence. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are being applied to analyze massive datasets, identifying patterns that humans might overlook.

Public engagement and education are essential for long-term conservation success. When people understand the incredible journeys undertaken by marine species and the challenges they face, they’re more likely to support conservation measures and make sustainable choices. Citizen science programs, where volunteers help collect data or monitor beaches, build personal connections to marine conservation.

The resilience and adaptability demonstrated by migrating marine species throughout evolutionary history provide hope. Many species have survived ice ages, warming periods, and dramatic sea level changes. However, the current rate of environmental change is unprecedented in recent geological history, making human intervention increasingly necessary to ensure these ancient migration patterns continue to connect our ocean’s diverse habitats for generations to come. Protecting these highways of the sea isn’t just about saving individual species—it’s about preserving the fundamental ecological processes that maintain ocean health and productivity for all life on Earth.