Beneath the waves, where tectonic forces meet the ocean floor, lies a world few have witnessed—a realm of fire and water, darkness and life. Submarine volcanic ecosystems represent one of Earth’s most extreme yet thriving environments.

These underwater volcanic systems challenge our understanding of life’s resilience and adaptability. From hydrothermal vents spewing superheated, mineral-rich water to sprawling lava fields teeming with bizarre creatures, submarine volcanoes create oases of biodiversity in the deep ocean. The study of these ecosystems has revolutionized marine biology, revealing organisms that survive without sunlight and thrive in conditions once thought impossible for life.

🌋 The Hidden Fire: Understanding Submarine Volcanic Systems

Submarine volcanoes form along mid-ocean ridges, subduction zones, and hotspots, creating geological features that shape the seafloor. These underwater mountains and vents are far more numerous than their terrestrial counterparts, with scientists estimating over one million submarine volcanoes exist worldwide, though only a fraction have been explored.

The process begins deep within Earth’s mantle, where intense heat and pressure create molten rock. When this magma finds pathways through the oceanic crust, it erupts into the cold ocean water, creating dramatic geological features. The interaction between superheated lava and seawater produces explosive reactions, rapid cooling, and the formation of unique mineral deposits that become the foundation for extraordinary ecosystems.

Hydrothermal Vents: Life’s Chemical Factories

Hydrothermal vents represent the most studied and fascinating aspect of submarine volcanic ecosystems. These underwater geysers release water heated to temperatures exceeding 400°C (750°F), loaded with minerals and chemicals from Earth’s interior. When this superheated fluid meets the frigid ocean water, it creates towering chimneys of mineral deposits, often called “black smokers” or “white smokers” depending on their mineral composition.

The chemistry occurring at these vents is remarkably complex. Hydrogen sulfide, methane, iron, manganese, and other compounds pour into the ocean, creating chemical gradients that specialized organisms have learned to exploit. This process, called chemosynthesis, replaces photosynthesis as the primary energy source for the entire ecosystem.

🦐 The Extraordinary Inhabitants of Volcanic Seafloors

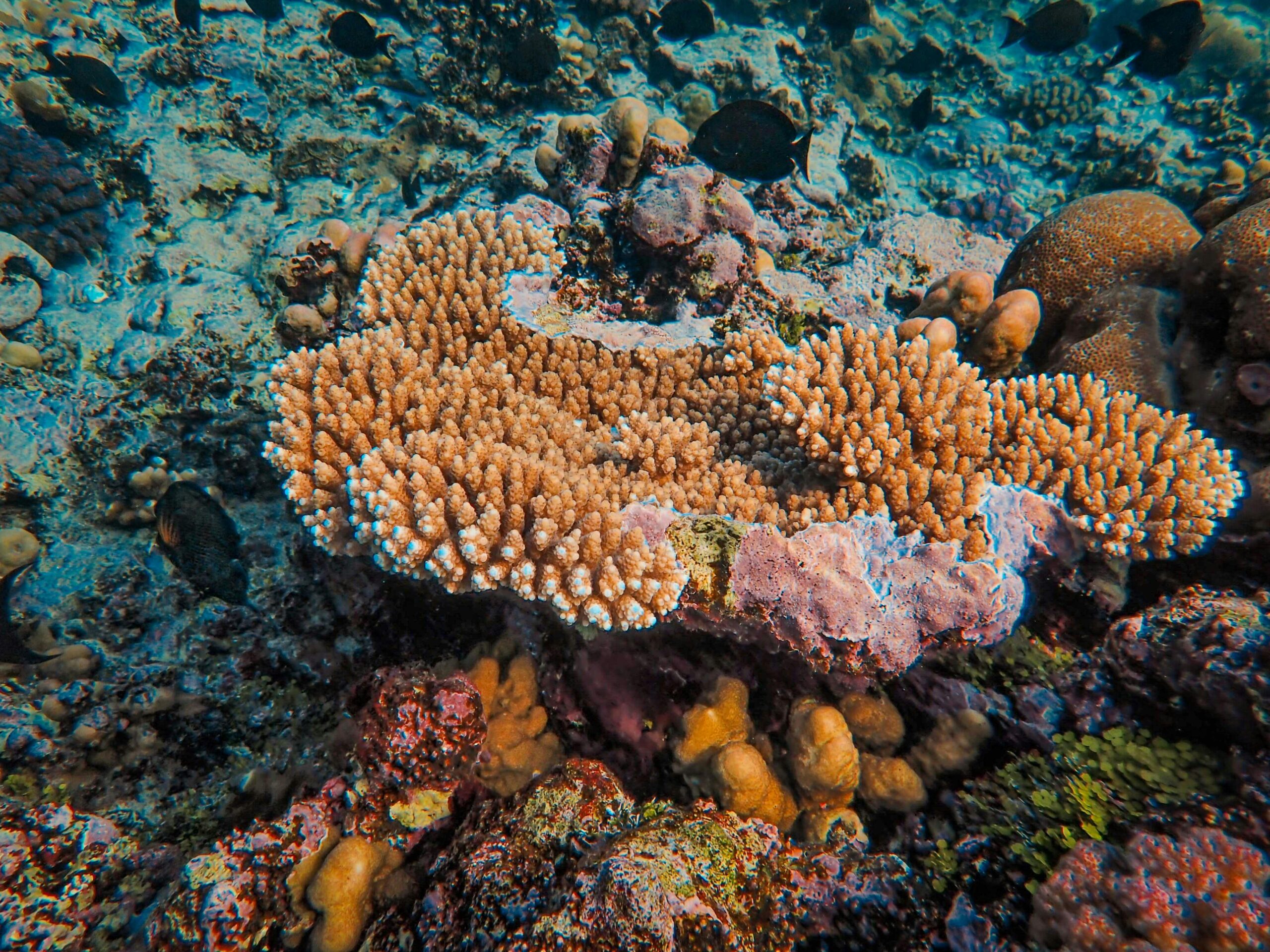

The biodiversity around submarine volcanic systems defies conventional biological wisdom. Organisms here have evolved remarkable adaptations to survive extreme temperatures, crushing pressures, toxic chemicals, and complete darkness. These creatures represent some of the most alien-looking life forms on our planet.

Microbial Pioneers and Chemosynthetic Bacteria

At the foundation of these ecosystems are chemosynthetic bacteria and archaea. These microorganisms oxidize chemicals like hydrogen sulfide and methane to produce energy, forming the base of the food web. Some bacteria create thick mats covering rocks and sediments, while others live symbiotically within larger organisms, providing them with nutrition directly.

These microbial communities are incredibly diverse, with new species discovered regularly. Scientists have identified extremophiles capable of surviving in temperatures approaching the boiling point of water, in highly acidic or alkaline conditions, and under pressures hundreds of times greater than at sea level.

Giant Tube Worms and Remarkable Invertebrates

Perhaps the most iconic residents of hydrothermal vents are giant tube worms (Riftia pachyptila). These creatures can grow up to 2.5 meters (8 feet) long and have no mouth, gut, or anus. Instead, they host billions of chemosynthetic bacteria within a specialized organ called a trophosome, receiving all their nutrition from these microbial partners.

Other fascinating invertebrates include:

- Yeti crabs with hairy claws that farm bacteria for food

- Scale worms covered in protective scales that reflect the vent’s heat

- Giant clams and mussels with symbiotic bacteria in their gills

- Blind shrimp that navigate using specialized heat-sensing organs

- Pompeii worms that survive at the highest temperatures of any complex organism

Specialized Fish and Mobile Predators

While less abundant than invertebrates, several fish species have adapted to life near volcanic vents. Eelpouts and zoarcid fish patrol the vent periphery, feeding on smaller invertebrates. These fish possess antifreeze proteins and specialized enzymes that function in extreme conditions.

Larger predators occasionally visit vent ecosystems, including octopuses, crabs, and even some shark species, attracted by the concentration of prey. These visitors remind us that submarine volcanic ecosystems aren’t isolated—they connect to the broader deep-sea environment in complex ways.

🔬 Scientific Discoveries That Changed Everything

The discovery of hydrothermal vent ecosystems in 1977 near the Galápagos Islands revolutionized our understanding of life on Earth. Before this discovery, scientists believed all ecosystems ultimately depended on sunlight through photosynthesis. The revelation that entire communities could thrive on chemical energy alone opened new possibilities for understanding life’s origins and its potential existence elsewhere in the universe.

Implications for the Origin of Life

Many researchers now consider hydrothermal vents as strong candidates for the birthplace of life on Earth. The chemical-rich, energy-intensive environment provides all the necessary ingredients: energy sources, protective mineral structures, and chemical building blocks. The “iron-sulfur world” hypothesis suggests that life may have begun at similar vents over three billion years ago.

This theory has profound implications for astrobiology. If life can originate and thrive at submarine volcanic vents on Earth, similar environments on other worlds—such as the subsurface oceans of Jupiter’s moon Europa or Saturn’s moon Enceladus—might harbor life as well.

Biotechnology and Medical Applications

Extremophiles from submarine volcanic ecosystems have become invaluable to biotechnology. Heat-stable enzymes from vent bacteria have revolutionized molecular biology, including the PCR (polymerase chain reaction) technique fundamental to genetic research and medical diagnostics. Other compounds show promise as antibiotics, anticancer agents, and industrial catalysts.

🌊 The Geography of Submarine Volcanic Activity

Submarine volcanic ecosystems are distributed globally, following the planet’s tectonic boundaries. Understanding their geography helps scientists predict where undiscovered vent communities might exist and how they’re connected across ocean basins.

Mid-Ocean Ridges: The Volcanic Highways

The mid-ocean ridge system stretches over 65,000 kilometers around the globe, making it Earth’s longest mountain range. Along these ridges, tectonic plates spread apart, allowing magma to rise and create new oceanic crust. This process generates numerous volcanic vents and associated ecosystems, from the Atlantic to the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Notable vent fields include the East Pacific Rise, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and the Juan de Fuca Ridge off the Pacific Northwest coast. Each region hosts unique communities with distinct species compositions, suggesting long periods of isolation and independent evolution.

Back-Arc Basins and Subduction Zones

Where one tectonic plate descends beneath another, volcanic activity creates back-arc basins with their own hydrothermal systems. These environments often feature different chemistry than mid-ocean ridge vents, with more acidic conditions and distinct mineral compositions, leading to different biological communities.

The Mariana back-arc basin, near the world’s deepest trench, hosts some of the most extreme vent environments discovered, with pH levels as low as 2.8—nearly as acidic as vinegar—yet still supporting diverse microbial life.

⚡ Energy Flow and Ecosystem Dynamics

Understanding how energy moves through submarine volcanic ecosystems reveals the intricate relationships sustaining these communities. Unlike surface ecosystems with clear day-night cycles and seasonal patterns, vent ecosystems depend entirely on the geological activity beneath them.

The Chemosynthetic Food Web

Energy enters the system through chemosynthetic bacteria converting inorganic chemicals into organic compounds. Primary consumers, including grazers and filter feeders, harvest these bacteria directly or obtain them through symbiotic relationships. Secondary consumers feed on these primary consumers, and decomposers recycle organic matter, releasing nutrients back into the system.

This food web is remarkably efficient compared to photosynthetic systems, with much shorter chains from primary producers to top predators. The concentration of life around vents creates high biomass densities, sometimes exceeding tropical rainforests despite the harsh conditions.

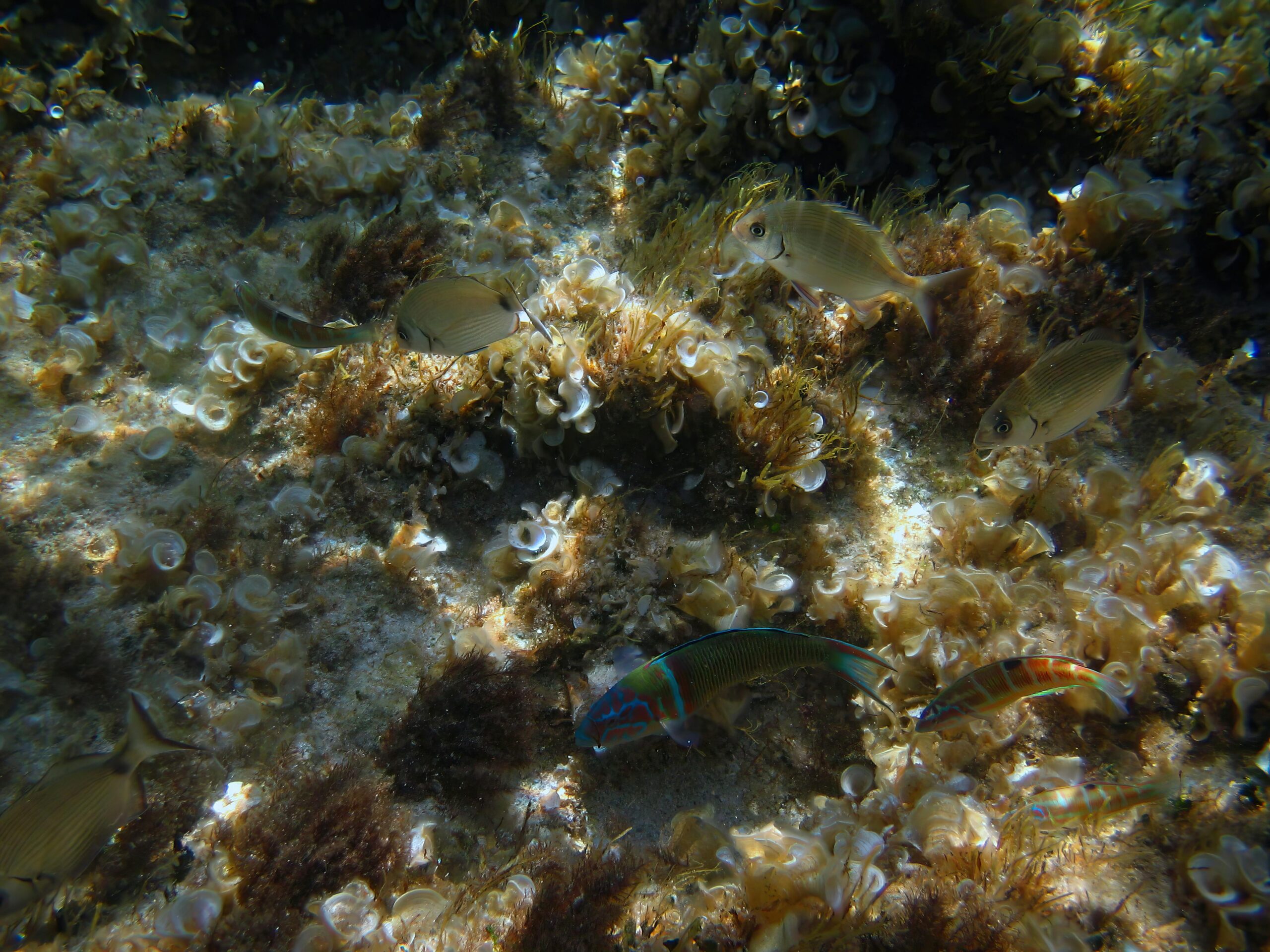

Vent Lifecycle and Community Succession

Hydrothermal vents aren’t permanent features. They can persist for decades or shut down suddenly as geological conditions change. This dynamic creates a pattern of colonization, maturation, and extinction that shapes community structure.

Pioneer species, typically fast-growing bacteria and small invertebrates, colonize new vents within days. As the vent matures, slower-growing species like tube worms establish themselves, creating more complex communities. When a vent dies, the community disperses or perishes, with larvae drifting in ocean currents seeking new active vents—sometimes hundreds of kilometers away.

🔍 Exploration Challenges and Technologies

Studying submarine volcanic ecosystems presents extraordinary challenges. These environments exist at depths where pressure crushes conventional equipment, temperatures fluctuate wildly, and visibility is nearly zero. Despite these obstacles, technological advances have enabled increasingly sophisticated exploration.

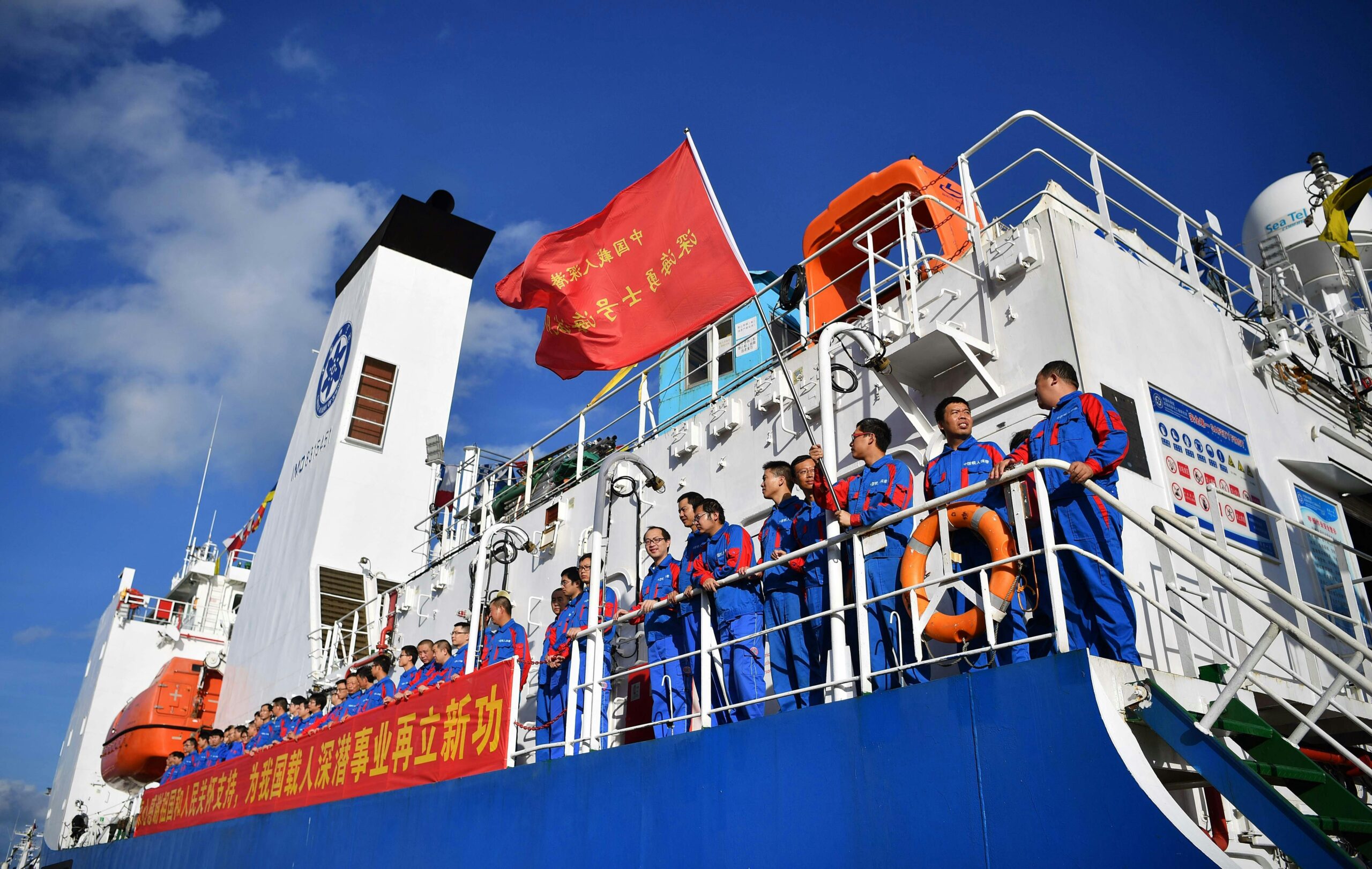

Remotely Operated Vehicles and Submersibles

Modern ROVs equipped with high-definition cameras, manipulator arms, and sampling equipment allow scientists to explore vent environments remotely. Manned submersibles like Alvin have carried researchers to these depths, providing direct observation opportunities that yield insights impossible to obtain remotely.

These vehicles have documented thousands of vent sites, collected specimens, and deployed long-term monitoring equipment. Each expedition reveals new species and expands our understanding of these ecosystems’ complexity.

Molecular and Genomic Approaches

Environmental DNA sampling and metagenomics have revolutionized vent ecosystem studies. Scientists can now catalog entire microbial communities without culturing individual species, revealing vast undiscovered diversity. Genomic sequencing of vent organisms uncovers the genetic basis of their extraordinary adaptations, informing both evolutionary biology and biotechnology.

🌍 Conservation and Future Threats

Despite their remote location, submarine volcanic ecosystems face growing threats from human activities. Deep-sea mining interests target the mineral-rich deposits around vents, potentially destroying these unique habitats before we fully understand them.

Deep-Sea Mining Concerns

The same mineral accumulations that support vent ecosystems attract commercial interest. Polymetallic sulfides containing copper, zinc, gold, and other valuable metals have spurred exploration for potential mining operations. However, mining would likely devastate vent communities, with recovery potentially taking decades or centuries—if recovery occurs at all.

Scientists advocate for protected areas around known vent fields and comprehensive environmental impact assessments before any mining proceeds. The unique biodiversity and scientific value of these ecosystems argue strongly for conservation over exploitation.

Climate Change and Ocean Acidification

While vent organisms tolerate extreme local conditions, broader ocean changes could affect their larval dispersal and connectivity between vent sites. Ocean acidification, warming, and changing currents may alter the delicate balance these ecosystems maintain with the surrounding ocean.

💡 The Future of Submarine Volcanic Research

As technology advances and exploration continues, submarine volcanic ecosystems will undoubtedly yield more surprises. New vent fields await discovery in unexplored ocean regions, each potentially hosting unique species and communities.

Emerging research focuses on understanding how these ecosystems respond to natural disturbances, their connectivity across ocean basins, and their role in global biogeochemical cycles. Long-term monitoring programs track changes over years and decades, revealing dynamics invisible in short-term studies.

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with exploration technologies promises to accelerate discovery. Autonomous underwater vehicles could map vast areas independently, identifying potential vent sites for detailed investigation.

🎯 Why These Ecosystems Matter to Everyone

Submarine volcanic ecosystems might seem remote and irrelevant to daily life, but they offer profound lessons and practical benefits. They demonstrate life’s incredible resilience and adaptability, challenge our assumptions about biological limits, and provide resources for medical and technological innovation.

These ecosystems remind us that Earth still holds mysteries—that vast regions remain unexplored and unknown. They inspire wonder and curiosity while offering practical benefits through biotechnology applications. Most importantly, they expand our perspective on what’s possible, both on Earth and potentially on other worlds.

The vibrant, mysterious world of submarine volcanic ecosystems represents one of our planet’s greatest natural treasures. As we continue unveiling their secrets, we gain not only scientific knowledge but also deeper appreciation for the extraordinary diversity of life on Earth and the importance of protecting these remarkable environments for future generations to study and admire.